Credit : Mirco Magliocca

Boris Godounov, Olivier Py, Théâtre des Champ Elysées

03/03/2024 - Classique News, Pedro Octavio Diaz

Just over two years ago, Europe was still living in relative peace, despite the ominous winds blowing from the East. Now winters, springs and summers have come and gone with their waves of life, while on the fertile plains of Ukraine, machine-gun fire rumbles and rifles replace the sweet song of the dumkas. Some would have us believe that Russia has been a barbaric country for centuries. The claim is overused, because such a vast territory has made its mark through fire and blood, but also through the brilliant genius of its artistic expressions, as sparkling as the first winter snow. Russian history has been punctuated by periods of great confusion, and perhaps the fatalistic flame so dear to its novelists has been nourished by the complex nature of its state-building. Following the longest reign in Russian history, that of the terrible Ivan IV (1533-1584), the very young nation became mired in nearly a century of chaotic divisions and internecine wars. It was finally in 1689 that Peter I, known as the Great, finally stabilised the institutional situation following the reforms of his father Alexis I, known as the “Most Peaceful”.

It’s a curious situation, this period known as the “Time of Troubles”, from which is drawn the straw that is used to stuff the scarecrow of extreme regimes. Neither revolution nor civil war, this period is above all traumatic for Russia as a time when the Russian nation and culture almost disappeared under the tutelage of the powers of the region, Sweden and above all Poland, which placed the country under its tutelage. This is the origin of the paranoid feeling against the West that “justifies” all excesses.

In 1598, the boyar Boris Godunov was crowned tsar, under the name Boris I. He reigned until 1606. He reigned until 1605, when he was ousted by the Poles and the exasperated people. His only legacy is that of a crude man who looked after his own interests and those of his caste. And this Boris I had a career that young politicians on the front pages of French magazines would only dream of: before becoming Tsar, he was Ivan IV’s “prime minister”. Even in times of crisis, ambitious small-minded people get their way, but not for long. The true nature of the cuistres becomes apparent when they reach the highest levels of responsibility. In the solitude of the summit, the wind blows hard and sweeps away even the hard-rooted weeds.

The often exaggerated life of Tsar Boris has been adapted in many ways, the best known being by the great Pushkin. Accustomed to glossing over and distorting all the historical figures in his writings for poetic reasons, the poet portrayed a Boris Godunov in torment and condemned him for the murder of the young Tsarevitch Dimitri, which he would not even have ordered in historical reality. Modest Mussorgsky took this historical tale and turned it into a monumental opera in 1869 – reworked and expanded in 1872. Mussorgsky was not the only musician to adapt the story of Boris I to opera: as early as 1710, Johann Mattheson wrote a very fine opera, which remained buried in German archives confiscated in 1945 until 2005. Mattheson’s Boris Godunov will see the light of day in Kiev, and will finally have its moment of glory in 2021 in Innsbruck.

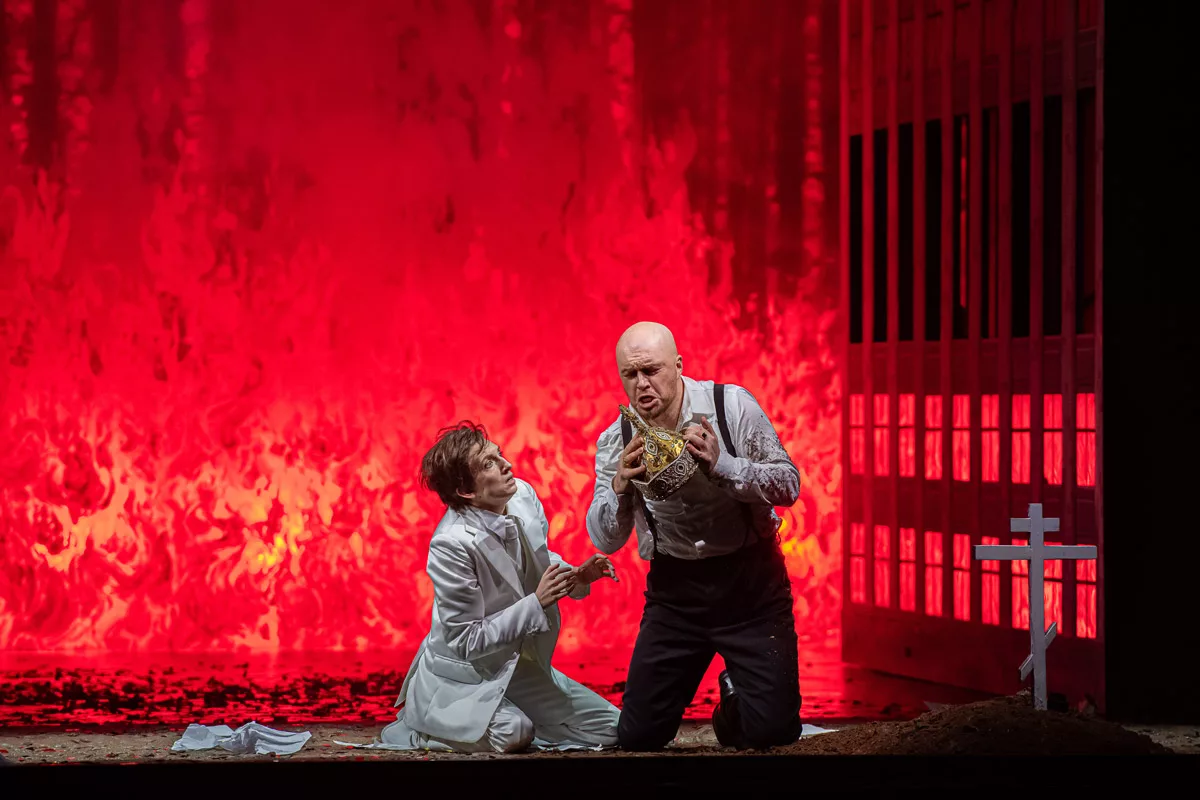

The Théâtre des Champs-Elysées plays host to the Théâtre du Capitole de Toulouse’s sumptuous production, premiering in November 2023. For the occasion, the plot of the 1869 version has been chosen for its more concise side. The production is directed by the great Olivier Py. He subtly makes references to the coercive and nostalgic present-day Russia, showing the undeniable link between the declining empire of 1605 and our own times. Each picture is painted with a sense of movement, the colours ranging from the gold of the icons to the crimson of the embers of revolt. The structures that make up the set follow the narrative with a luxury of atmosphere that leaves you breathless. The singers have a feel for the lines, their gestures are supple and it is easy to grasp the drama of Tsar Boris.

Alas, Andris Poga’s conducting failed to awaken the slightest nuance and this is a great disappointment, especially in the case of Mussorgsky’s thousand-coloured score. One regrets that boredom seemed to set in with an overly monotonous choice of tempi, drowning in the large pages of each tableau as if in an ocean of peat. The Orchestre National de France lacked enthusiasm, which in the end is not surprising from a tired institution with clumsy, nonchalant reflexes. On the other hand, the Opéra National du Capitole Chorus are remarkable, lively, intelligible and highly cohesive. The choral pages are a musical highlight, and it is a pleasure to rediscover the composer’s grandiose pen.

Andris Roslavets replaces Matthias Goerne and is a decent Boris, albeit a little scholastic at times. Opposite him, Airam Hernandez’s ‘false Dimitri’ Grichka has a very fine tenor voice, but also remains a little in the background when his veiled role could have pushed him a little more into agility. Of the entire cast, two roles really shone. The divine Xenia by Lila Dufy, whom we had already noticed at the Voix Nouvelles 2024 competition. With a rich, brilliant timbre, she did justice to this too-short but magnificent role. The young heir, Fiodor, was played by Victoire Bunel, whose agility and phrasing, as well as the beautiful colour of her timbre, we cannot praise enough.

It was a subdued evening for a story as dark as the past in which it lurks. And yet Boris I is the perfect anti-hero, the ambitious man punished by his own demons. It’s a wise warning to future political apprentices who are only climbing, without seeing that the precipice is always closer to the top than to the bottom.